You are Your Best Thing

From Cheng's Ornamentalism to my "hybridization," - philosophies for neoliberal feminism's many failures

“From the divergence between black flesh and yellow ornament, we have arrived at this convergence: flesh that passes through objecthood needs ‘ornament,’ to get back to itself.”

(Ornamentalism: A Feminist Theory for the Yellow Woman)

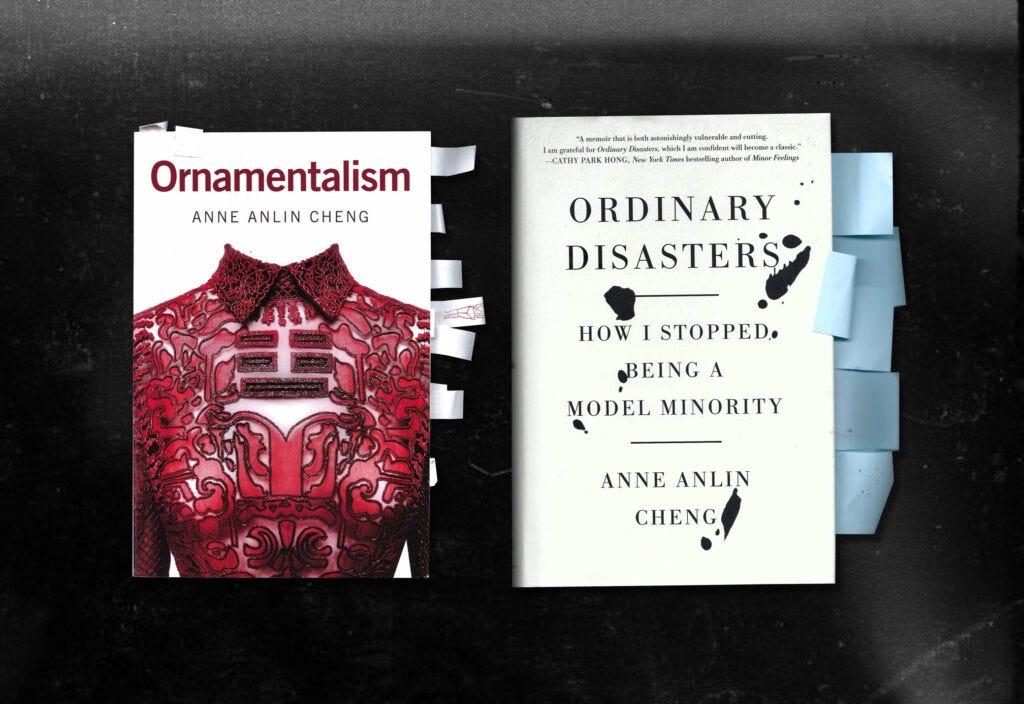

Anne Anlin Cheng’s 2018 Ornamentalism—as it builds from her earlier scholarship including an eponymous 2018 article published in The University of Chicago’s Spring 2018 edition of Critical Inquiry—opens with a provocation: “We say Black women, brown women, white women, but not yellow women.”1

The Main Thing: Ornamentalism

She evokes what Fanon called the “epidermal racial schema,” in foregrounding what will become a novel epistemology of race that places Asian women at the center, highlighting what visual culture and theoretical omissions might reveal about the limited language of racialized femininity as beholden to flesh and skin, and stretching critique past the terms of “objectification,” “orientalism,” and “agency,” into a new territory that connects art, to culture, to law, and politics.

“You are your best thing,” Cheng quotes from Beloved …

“Instead of considering what it means for a person to have been turned into a thing with an implicit nostalgia for that lost subject…

we must also consider the reversed process whereby things have been made into persons…

revealing the fundamental logic of abstracted decoration that constitutes the category of personhood in the first place.” (p. 446)

In initiating her project, Cheng alerts us to a vernacular comfortability with essentialism along certain intersectional, lines, and directs us to what has become practically “inadmissable,” as it constitutes a “theoretical black hole,” in social, political, and aesthetic disciplines.2

Ornamentalism asks then what we might gain from correctively attending to the “yellow woman,” and her ontological construction across visual culture, along her own peculiarized terms. Cheng lands on a new “aesthetic ontology,” that comes in taking the yellow woman seriously.

From this provocative initiation, emerges—in my view—one of the most generative contemporary philosophical interventions interested in race and gender I have encountered as it troubles all of the ways we have come to think about “women of color,” their position, and all our dominant strategies for correcting what we have come to identify as historical abuse or, rather, injustice.

More than a history of the yellow woman’s visual construction, in its theory of personhood and therefore human “agency,”—that is, if we are to be concerned with agency at all—Ornamentalism provides a language and theoretical framework against which I am able to settle my own uncomfortability with neoliberal feminism and its terms.

As a student of both political theory—by way of Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, by way of Social Studies—and aesthetics—by way of visual culture by way of art history—for me, Ornamentalism even offers a new way of thinking about globalization, citizenship, and presently, the Middle East as the United States continues armed conflict in the region which I have known to be a perpetual involvement throughout most of my life.

Ornamentalism’s applications are multiplicitous, but first we must contend with its argument along its established terms and its utility within the discipline from which it emerges. First we must talk about ornamentalism as an aesthetic theory, from black women, for yellow women, and then as it might return to black women again.

“Now to what extent is this bifurcated condition of being human and nonhuman always already the condition of being black and a slave?

Why do we need ornamentalism to think about black female objectness?

Because it names the aesthetic and inorganic entanglements repressed by (yet critical to) a history of human materialism.” (p. 444)

The Agency Thing: Subjectivity

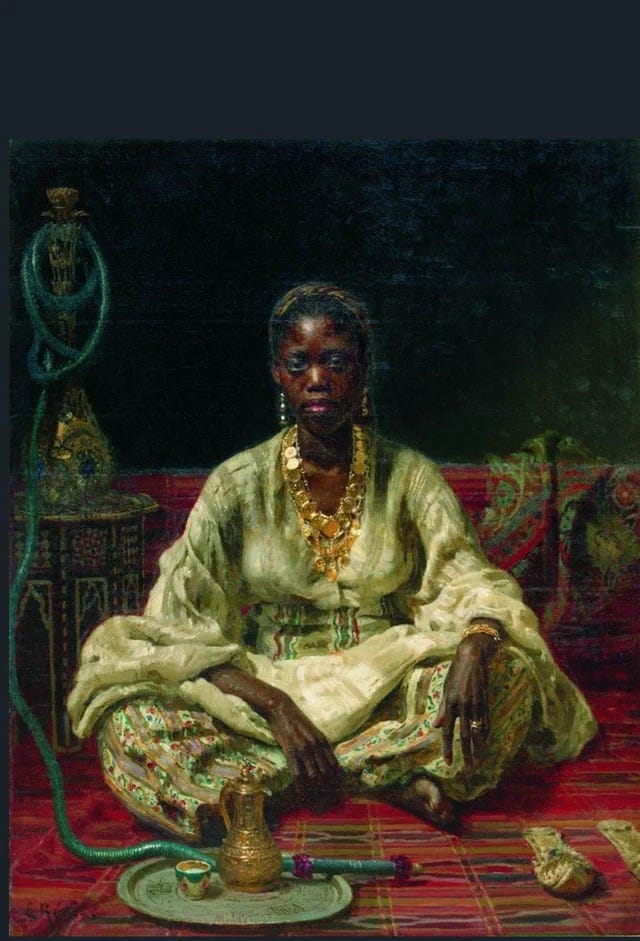

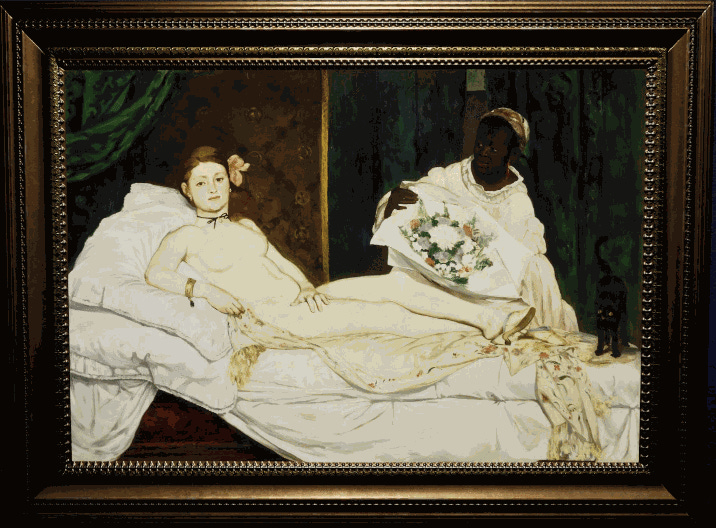

I encountered Ornamentalism in a course covering Race & Aesthetics for Juniors writing related theses in Harvard’s HAA department. I began to develop an understanding of the work abstractly, I read it in the same week I read Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby’s 2015 “Still Thinking about Olympia’s Maid,” and Cécile Bishop’s “Portraiture, race, and subjectivity: the opacity of Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait d’une négresse.”

The former troubles the “overlooking,” of the black maid depicted in Manet’s Olympia and of the model herself, Laure, who posed for the painting, in service of exploring how the painting depicts modernity by capturing both “France’s long reliance on slavery in the Caribbean,” and “its Revolutionary redefinition of all blacks as paid workers after the second abolition of slavery in 1848,” attending to what the maid, as both black and woman, illuminates about the modern France Manet depicts.

The latter, explores the “crisis of visuality,” in how Benoist paints his negresse, honing in on his treatment of her skin. Bishop complicates the disciplinary binary in reading this controversial painting as either humanizing or objectifying, centering how it challenges the binary of subjecthood and objecthood that was necessarily muddied by the racialized slave system abolished in France by the French revolutionary government in 1795 and reinstated two years after the work’s completion.

Bishop—building upon Glissant’s notion of opacity and centering the treatment of the subject’s black skin and face—explores the transparency demanded from white female subjects as condition for their subjectivity, against the constructed opacity of the negresse’s skin.

This is the way I began to understand Cheng’s work in its reference to her past scholarship on black womens’ skin and in its concern with the subject-object paradigm to begin with: questioning if the two were ever extricable in the case of the yellow woman or the black woman, whom she argues were not included in the construction of the Enlightenment subject instead shaping its form by their exclusion.

I thought about the pre-Kantian self and the post-Kantian self. I considered the 18th-century self: fragile, relationally constituted by occurrences and the objective. Then, I considered the 19th-century self as it came to be understood as preeminent and imposible through acts of “agency.”

Cheng motioned me toward the question of whether we—colored women—should be concerned with this agency at all: this Enlightenment agency for the Enlightenment subject, contingent on a particularized status of subject-object relations that this scholarly body argues to be both racially exclusive, and necessarily limited.

“Why Did We Leave Zanzibar?”

by: Barbara Chase-Riboud

Dark haloed sister

Penumbric jewel

Burning in dry tobacco leaf beauty

Brittle and flaking discontent

Eyes damned with the slit of disappointment…

Long-fingered, long-necked

Delicate wristed and ankled sister

Wide-hipped and smelling of honey

Eyes echoing hollow words and unremembered places

Fingers stuttering, tearing

And wrapping themselves around

This essential question:

Why did we leave Zanzibar?

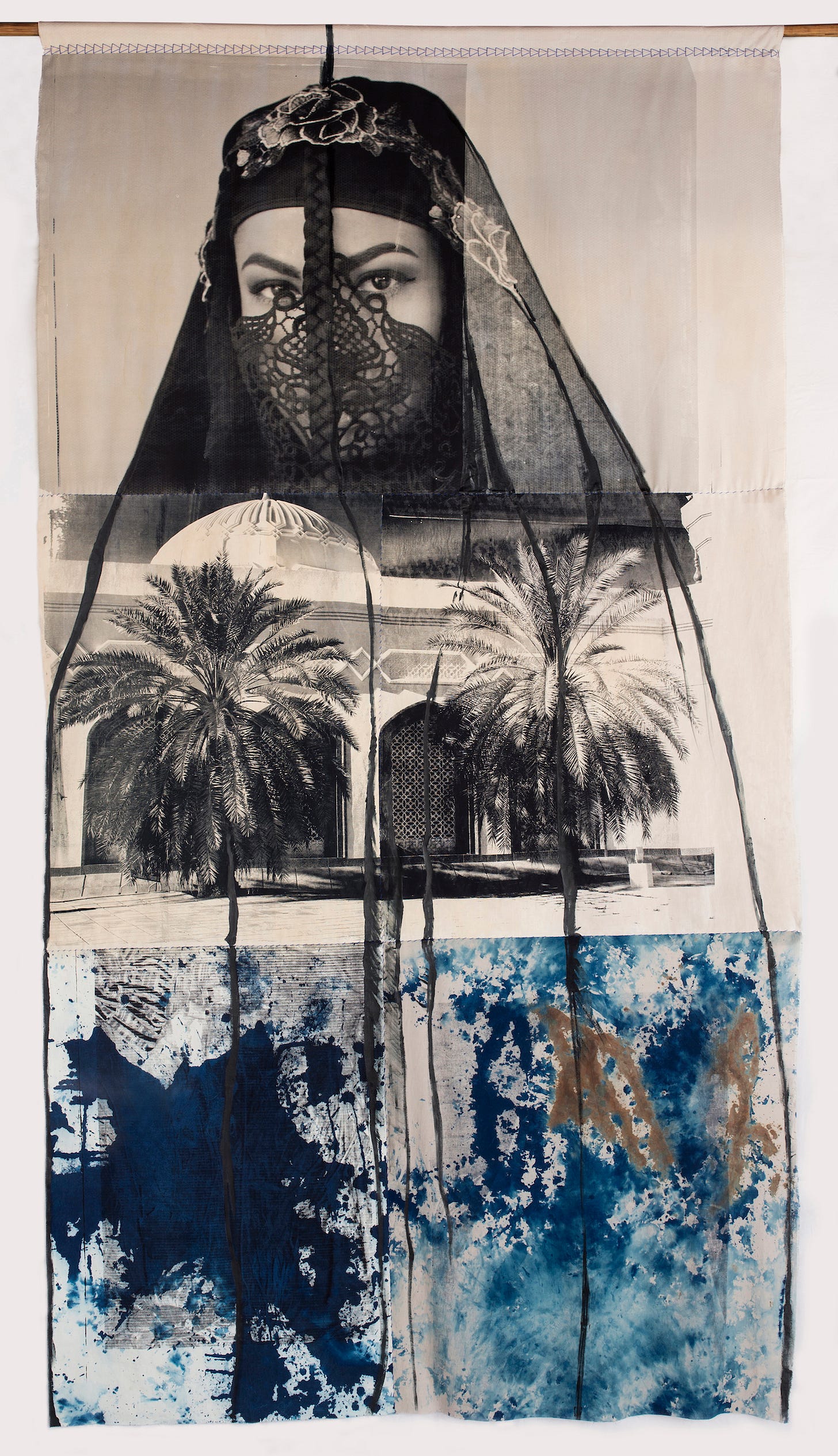

I thought back to my sophomore year of political theory and our week of Saba Mahmood’s Politics of Piety, a breath of fresh air in our syllabus. I wrote my sophomore Social Studies paper on using Zora Neale Hurston’s veiling as applied to Janie in Their Eyes Were Watching God: a racialized and gendered subject, to triangulate a reading of Du Bois’s veil as metaphor and Mahmood’s veil as metonym.

This is when I really started to understand Cheng, and I ended up using her Ornamentalism as a theoretical signpost against which Adrian Piper’s Mythic Being might be understood as a similar “collusion between abstraction and racial embodiment.”

My Junior Paper in Harvard Art History

As promised in my recent roundup, I’m sharing my final paper from Harvard’s History of Art & Architecture Junior Tutorial in Race & Aesthetics for Quiet Patrons. This paper explores Adrian Piper’s Mythic Being and builds on Anne Anlin Cheng’s Ornamentalism

My Hijab Thing: Hybrid Intuitions

As a little girl, I had a hijab phase. Raised in a Great Migration Baptist church, I knew from a very young age that a relationship with God necessitated a relationship with beauty, poetry, musicality, and culture. When the hijab was explained to me in Indianapolis Public School #359 as an “outward expression of an inward commitment,” or some adjacent version of the patronizing shorthand adults employ to explain to children all those things which they themselves do not necessarily understand, I wondered why weren’t all good Christians hijabis?

I wondered if anyone had taken the time to explain this to the women in big extravagant hats and lace gloves at my Sunday services who clapped along to the music because snapping was secular, and who, on one occasion, even passed me a modesty cloth to cover my knees such that the pastor would not be distracted by them as they were exposed in the first pew.

I was so curious that I spent a great deal of time researching the hijab on my family’s desktop upstairs. How could our faith be so incense and myrrh, praise-dancing, flag-spinning, whirlwind patchwork of all we’ve carried in migration; how could our faith be so black Jesus overpainting, songs, prayers, sayings, scriptures, memorized and spat back like slam poetry; how could Easter Sunday be so hot-comb doily socks; how could my church have a mime ministry and no hijabis?

I learned in the best way I learn, through doing, and my research culminated in “DIY hijab,” tutorials to satisfy my hyperfixation. Then, after doing, I wrote about my doing: I wrote a long paragraph to my mother confirming my newfound commitment to my Christian faith, and therefore announcing my very short-lived seemingly-natural embrace of the hijab.

My hijab, sensational and feminine, I made from purple beaded fabric from my plush cream sewing box at the top of my closet. Then, I photographed myself. Allegedly. Repeatedly. Returning to these images, which, for all intents and purposes I will say do not exist, is still very funny.

There is, of course, the immediate humor of such a peculiarly precocious child, in her naïveté, curiosity, and content closed-mouth smile. Then, the image(s, alleged though they may be) which are funny because transgression is funny.

This type of innocent, well-meaning transgression, against the present context of “cultural appropriation,” and “woke,” is very funny in fact. Funny, because you’re not really supposed to laugh, though a little laughter is okay because the images can be explained: me, all earnest in intent, and the public education system, all to blame.

Ha ha.

Cultural hybridization was intuitive. I felt that my faith was sensual and I searched for beautiful practices that highlighted the best of what was my own to identify with.

One of my more imaginative public fictions that I disseminated from pre-kindergarten through early middle school, or, otherwise, one of the ridiculous lies I told that do not really count as lies because I made them believably outrageous and because other, less sentient children only half-believed me—I hope—was that I was going to have a quincecañera that was going to be extravagant and opulent and anyone who crossed me would most definitely not be invited.

I was drawn to the ornate beauty of women’s rituals around the globe, and felt a certain freedom in trying them on even as mere imaginative exercise.

This would be an easy thing to dismiss as childhood misunderstanding of cultural etiquette or a worldly active imagination that is now seemingly in poor taste, but I wonder what such an attraction reveals about distinct ethnic feminine experiences and the politics of hybridized exchange.

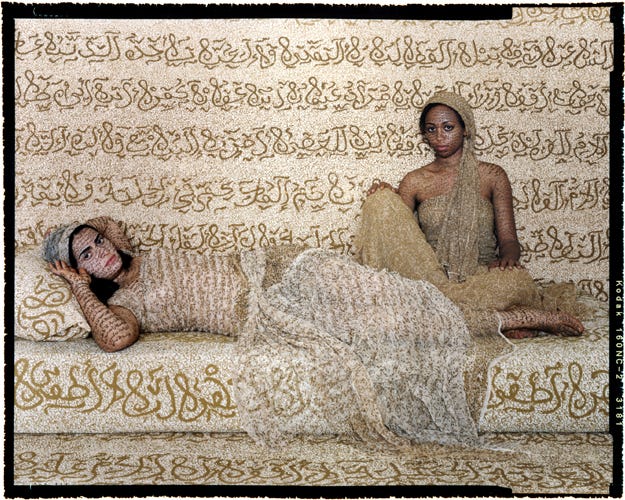

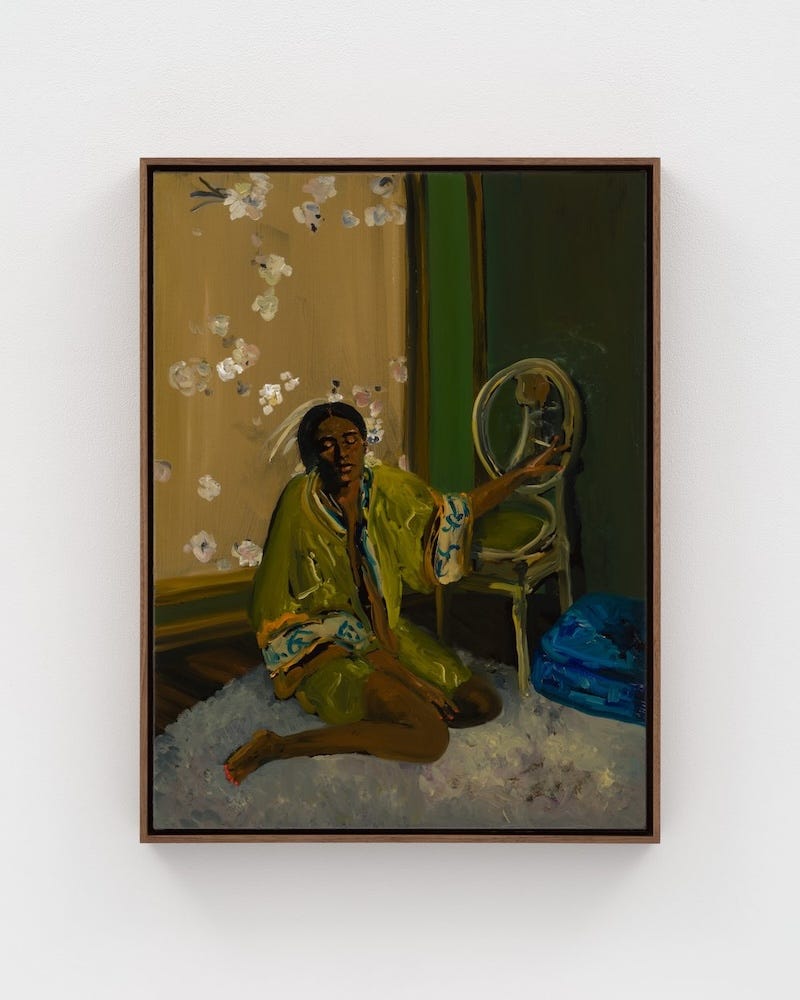

When I first decided I wanted to write about Ornamentalism in the free time I use to maintain my writerly practice vis a vis this lovely poets’ studio, newsletter, and documentary space, it was because I was interested in the oriental motifs recurring across the paintings of Danielle Mckinney that reflected a similar line of questioning.

Mise-en-Scène: Things of Scenery

Oriental motifs of tapestries and screens and robes and delicate China featured prominently in the paintings of Mckinney’s Quiet Storm show at Marianne Boesky from the porcelain of Memoir to the silk robe of She to the fan of Tell Me More to the delicate tea set of Easy Over to the blue-and-pink cup of Oolong and a Spirit or the brocade patterns of Yesterday.

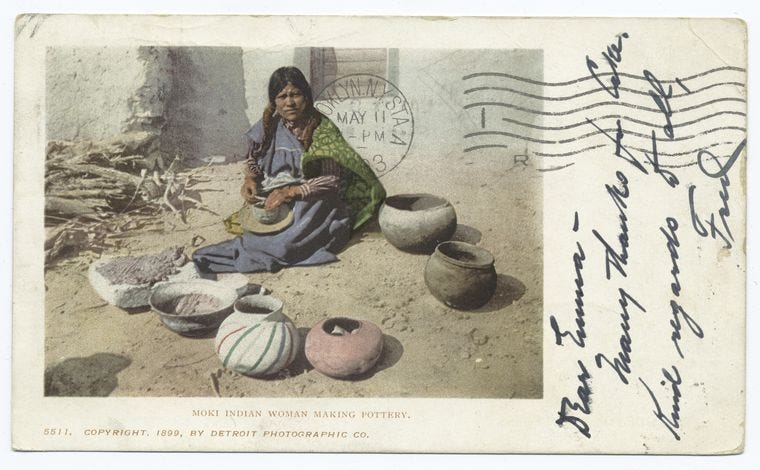

Evening Star depicts a seated woman in a silk robe afront a yellow chinoiserie screen wherein the white brushstroke of a peacock’s feather could almost be a feather in the woman’s hair.

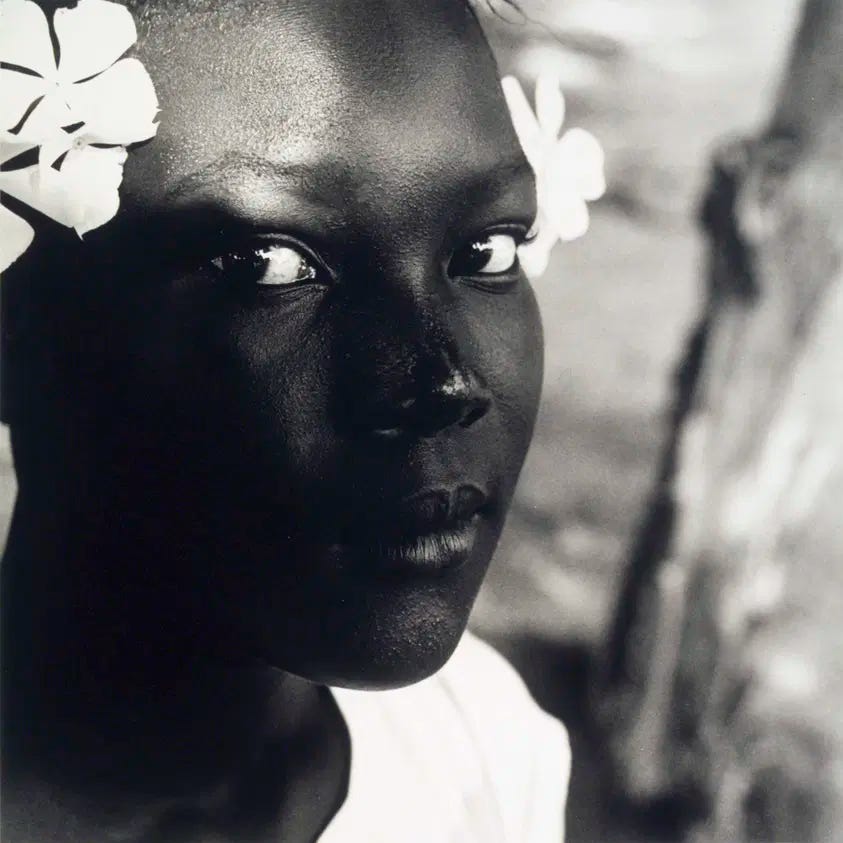

The woman smokes with her eyes closed in meditative stillness, her pose and surroundings recalling a hybrid of orientalist and primitivist tropes: flattening 19th-century chinoiserie and the framing of photographic and painterly portraits of indigenous women in colonial ethnographic images into a singular visual artifact of the darker-skinned woman.

This black woman is thus entered into a long visual history of racialized femininity without any ethnic over-relegation, embracing overlap and rejecting ethnically essentializing boundaries. She hones in on the history of seeing women her color, regardless of their ancestry.

In Evening Star, the depiction of Black women through the gaze of white artists, the positioning of indigenous women within primitivist fantasies, and the ornamental curation of Asiatic femininity all coalesce into a singular product.

Immediately, this painting returns me to Cheng and her argument that subjectivity and objectivity are fungible.

For Cheng, escaping objectivity is a futile aim, as the racialized female subject is so constructed that her subjectivity is predicated on objecthood itself.

For T Magazine, M. H. Miller wrote on Mckinney’s work and the politics of her showing of “black women with black skin.” Miller historicized “the canon of Western painting,” as including too few portraits of black women, and invoked Manet’s Laure, as most do, when citing the canon’s depictions of black women.

Miller cited Lorraine O’Grady’s “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Subjectivity,” and just as O’Grady highlighted how Laure was marginalized from subjectivity as a stabilizing co-construct to the West’s female body, Mckinney points to Cheng in articulating this co-construct’s nature.

Skin is important, to Cheng and Mckinney both, and Evening Star argues for a representational continuity in the hybridized observation of women with darker skin across their intersecting representational tropes and despite their divergent objective narratives.

In the text, Cheng emphasizes the importance of mise-en-scène, or the arrangement of props and costumes in conveying the yellow woman’s essence. These deliberate arrangements of objects are targeted at triggering certain meanings across their visual history.

Lacquered screens, porcelain vases, silk, and feathered fans have been used to evoke a slow, meditative femininity that was at once delicate and decorative. Objects are loaded, they have been used to strip agency and inflict wound, but for Cheng agency is not the important piece: the objects are.

From these objects, Cheng argues, Asian women have been co-constructed, and these objects have been used across painting to signify the woman’s nature even as they frame the non-Asian woman or without the presence of any woman at all: therefore performing racialization through their material object-ness and encouraging a slow gaze to linger on sensual, foreign bodies like objects themselves.

With the application of such oriental mise-en-scène as ornament upon the figure of a visibly black subject, Mckinney suggests a radical reformulation of the politics of black femininity and highlights a genre of representing black-skinned women that is often overlooked in its current perceived bad taste.

Things of the Past

Consider the image of Josephine Baker in 1935, posed regally, head half-covered, in an opulent silk sari designed by Elsa Schiaparelli inspired by Princess Karam of Kapurthala.

Consider then the delicate pink shawl Aretha Franklin was photographed wearing on her 35th birthday at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Then, perhaps, recall Donyale Luna, the first black supermodel, and the rare image of her and Salvador Dalí at a dinner party in New York City.

The year is 1975 and her curly hair is slicked back into a ponytail. She is sporting a massive gem bindi and a belt of Japanese characters. What do we make of this image now along the terms of our time— this supposed “cultural appropriation,” or “cultural fetishization,” by a black woman, too distasteful to theorize, its context too foreign to critique? We erase the images. We collectively forget.

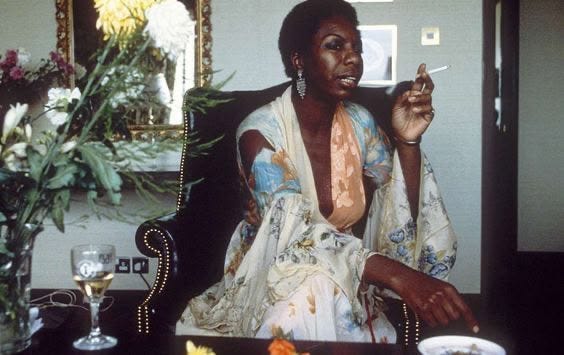

Consider the image of Nina Simone by Michael Ochs with her cluster of purple orchids, and humor me in assembling this catalogue of black women with oriental mise-en-scene. Maybe then think of me, well meaning, in my purple beaded hijab. What do these acts of ornamentalism by black women mean when their ornamentation is of a different tradition?

In the final pages of her Critical Inquiry article, Cheng returns to “the juxtaposition between Asiatic and Africanist femininity with which [her] essay began,” in order to “reconsider the paths of their divergence.”

Cheng, in her reflective assessment, began the essay, and thus in many ways the articulated project of Ornamentalism as such: “by distinguishing the wounded, flesh-laden black body from the immaculate, synthetic, ornamental yellow body.” (p. 443)

She has chronicled an “alternative logic of racialized embodiment that is also not necessarily enfleshment,” and found that “the body of labor (sexual, reproductive, economic) exemplified by the black female body — ungendered and excluded from the realms of kinship, state, and aesthetic value— is nonetheless not wholly alien to the practice and afterlife of ornamentalism.” (p. 443)

Otherwise, Cheng concludes, “ornamentalism may help elucidate for the black woman a set of different though related issues about the fraught convergence of material violence and aesthetic congealment.” (p. 443)

Beloved Things

In order to articulate these “different though related issues,” about black womanhood between material violence, first Cheng asks “how can we possibly talk about decoration or style in the face of the unimaginable corporeal brutality enacted through the history of slavery?” and decides it is fitting to approach this question with the invocation of Toni Morrison’s Beloved and all its “vivid and literal instantiations of… ‘hieroglyphics of the flesh’.” (p. 443)

“We are reminded that the black woman has been ‘decorated’ by culture and law in very specific and corporeal ways,” and Cheng explores the fleshly violence, the aesthetic and the abstract as they coalesce across eruptions described in the literal and the allegorical, of Beloved.

Cheng zooms into Sethe’s scarred back as it makes her both human and a tree in the metaphor that addresses it, Sethe is “a hybrid being whose personhood applies tremendous pressure on our notions of what constitutes living versus surviving.” (p. 444)

This bifurcation is essential to slavery, yes, but ornamentalism names aesthetic and inorganic entanglements necessary to human materialism.

The law speaks through abstraction and disembodiment, Cheng borrows from Barbara Johsnon to argue, and continues that “the dehumanized body might actually require objectness in order to subsist.”

There is no fleshly zero degree of conceptualization, as even flesh contains inscription itself.

“Insofar as the fantasy of the organic flesh has remained the single most cherished site of feminist and racial redemption, it has not been able to contest our assumptions about the basis for ontology, or how object life challenges whole sets of aspirations about individualism, freedom, agency, and self-possession.” (p. 444)

Cheng motions toward ecology, looking to conversations about blackness and animalism as they might be triangulated “by another category of being,” across plant life as “an allusion to the perverse life produced by the ecology of the plantation.” (p. 444)

Cheng cites Monique Allewaert in her suggestion that plantation ecology might “chart ‘an emerging minoritarian colonial conception of agency by which human beings are made richer and stranger through their entwinement with…colonial climatological forces as well as plant and animal bodies,’” and it is through this lens I suggest we might read the recurring insect motifs of Mckinney’s paintings as well.

“The question is no longer how we can think about aesthetics in the face of violence but how we could not…” (p. 445)

Essentially, Cheng is saying that flesh “defiled and radically severed,” from intrinsic humanity requires mediation on its pathway back or, otherwise, “flesh that passes through objecthood needs ‘ornament’ to get back to itself.” (p. 445)

It is along these lines that Cheng explores Baby Sugg’s sermon on self-possession as it must be courted and the self must be reassembled, concluding that the argument for self-love in Beloved comes down to Paul D’s famous advice: You are your best thing.

To “reconceptualize personhood for unmade persons,” Cheng argues that just as feminists commit to the flesh to unmake the taxonomy of gender, we must commit to the object if we are to undo and suspend the taxonomy of the human.

“In our eagerness not to abandon the flesh, we have not been willing to attend to life’s a priori enmeshment with nonlife.” (p. 446)

“You are your best thing,” Cheng drives her project home with the proposal that “instead of considering what it means for a person to have been turned into a thing with an implicit nostalgia for that lost subject… we must also consider the reversed process whereby things have been made into persons… revealing the fundamental logic of abstracted decoration that constitutes the category of personhood in the first place.” (p. 446)

Still, what can be said for the genre of black women building out their visuality with borrowed ornament? What are these women striving toward? What is their strategy? So what?

Brown-skinned Things

When I read “the body of labor (sexual, reproductive, economic) exemplified by the black female body—ungendered and excluded from the realms of kinship, state, and aesthetic value,” I recoil. Though I understand what Cheng is referencing, I am curious about what is ommitted when we naturalize this summary of seeing black women.

Just as “ornamentalism can name a particular mode of being that applies pressure on the fantasy of corporeal integrity,” when applied to black woman at the site of fleshly injury and adornment, I wonder how might we also interpret the sight of black women using oriental ornamentation to apply pressure to the fantasy of racial integrity and the unstable color categories from which such identity is often derived.

What do we do when history tells us that the orientalist includes visibly black women through women with brown skin.

To explain what I mean, I will return to Danielle Mckinney’s worldly black women. Just as quickly as the sight of a black woman in painting might recall Laure, Olympia’s maid, rendered flat, face cast into shadow, as she stands unsexed counterweight to Olympia herself, Mckinney asks that we consider, in a somehow parallel way, other depictions of colored women as similarly capacious sites of subjugation and fugitive agency.

Beyond this, Mckinney’s darkskinned women and their oriental details connect the visual histories of various darkskinned women, sifting through intersecting visual legacies for what uncomfortable vestiges and agentic seeds remain.

Across her ladies, clothed and nude, with the addition of all their ornamentalist mise-en-scène, particularly those ecological and oriental details, we are asked to recall at once the darker skinned ladies of Gaugin’s Tahiti or Matisse’s Morocco, just as quickly as the sight of a darker-skinned woman makes us think of the unsexed African eunuchs of Ingres’s odalisques or Benoist’s negresse.

The visual history of darker skinned women is not so black-and-white, as it were. We might even consider from Mckinney images of European women with similar ornament like Camille Monet as La Japonaise, asking what her red kimono and the fans tacked behind her alter about her femininity and subjectivity.

from “Voyage of the Sable Venus”

By: Robin Coste Lewis

…

Bust of a Nubian Prisoner

with Fragmentary Arms

Bound Behind Funerary

Mask

of a Negro with Inlaid Glass

Eyes

and Traces of Incrustations

Present in the Mouth

Censer in the Form of a

Nude Negro

Dwarf Standing with His

Hands

at His Sides upon an Ornate

Tripod

and Supporting on His Head

a Small Cup

in the Shape

of a Lotus

Flower

…

An outstretched black woman, reclining, semi-nude, in one of Mckinney’s small frames could just as easily rhyme with Gaugin’s Manaò tupapaú— in which a deep brown-skinned Tahitian woman lies, observing the viewer on a luminescent cream sheet in a room of velvety blues and purples and pinks while a spirit stands watching— as Manet’s Olympia, which illuminates what we understand and what we omit from the hybrid visual history of brown-skinned girls.

From Mckinney’s Table for Two, with its lady draped in white and blue, standing regally over a set of china echoing the colors of her draperie, we might consider James Abbott McNeill Whistler’s Purple and Rose in assessing how Mckinney pulls from objects and textures associated with the orient to ornamentally fashion a hybrid black woman.

For these hybridized black women perhaps aesthetic labor and worldliness constitute then a claim to selfhood and beauty becomes thus a language for power. Perhaps Mckinney is showing us a way toward alternative femininities and feminisms that prioritize colored women and exalt our cultural offerings, linking us as subject-objects to a world of commerce and exchange, and constructing a fuller black womanhood through object itself.

We could write off Nina Simone and her purple orchids and her silk robes as a coincidental hybrid, or Josephine Baker and her sari as dated and fetishistic, or me and my hijab as transgressive and naive, but I think its more interesting to probe these acts of hybrid affinity for what they reveal about the limitations of our cultural thinking, their origins, and new avenues for living as a responsible woman, a colored woman, a cultured woman in our irreversibly globalized world.

“Ornamentalism identifies both an epistemology and its fugitive meanings—

both instrumentality and unexpected opportunities. It is tied to the practice and aesthetics of Orientalism, but it also offers a critical framework beyond the assumed racial categories and periodization implied by terms such as Orientalism, primitivism, and modernism.

Our Best Things

By opening up a broader and historically deeper set of inquiries about how the aesthetic entails the political and how the political entails the aesthetic… it is precisely at the interface between ontology and objectness, animated by the ornament, that we are most compelled to confront the horizons and the limits of the politics of personhood.” (p. 446)

Building from the last paragraph of Ornamentalism, the paper, I believe it is worth asking a similar question about how hybridized self-fashioning from black women forces a confrontation of the horizons and limits of culture as we understand it in the way of the “Culture,” chapter in Kwame Anthony Appiah’s The Lies That Bind.

How might the transgression of borders by borrowed mise-en-scène reinforce cultural ownership by denaturalizing cultural hegemony, pressurizing corporeal integrity, and exposing reactionary cultural protectionism’s insufficiency as a strategy to cope with the destructive forces of neoliberal globalization: namely globalization’s culturally homogenizing forces across culturally hegemonic and uneven terms.

How might these acts of exchange direct women toward other ways of being, other agencies, other ways of interacting, that might be more sufficient than neoliberal feminism’s fetishization of agency, ownership, self-ownership, agency as ownership, and therefore its necessary essentialism that is simply not enough?

“For a long time now the concepts of Asian authenticity and of Orientalist commodification have remained our only safeguards against the vice of racist consumption.

But neither the longing for the former nor the allegation of the latter can address the complex relations between appropriation and susceptibility, or between embodiment and style.

Moral outrage in the face of consumption or fetishization, however warranted, cannot address or relieve the truly striking, idiosyncratic, and passionate exchange between thingness and personhood into which a display like this draws us” (p. 427)

I believe there are more careful practices of cultural stewardship beyond reactionary isolationism and appropriative free-for-all. Like with most things, the best practice is somewhere uncomfortably in between.

I wonder if there is a new approach to the failed “intersectionality,” highlighted by the bad taste neoliberal third-wave feminism’s essentializing language and hasty solutions leave in a lot of black women’s mouths. I wonder what hybridization, and the historical practices of marginalized women in self-advocacy from organizing to the veil reveal about gender justice from our unique vantage.

I wonder what new art histories a hybrid vision of race and color allow us to contextualize and understand. I wonder how we can think about the recoil from borders at both extremes of globalization, and the benefits of culture while understanding the limits of essentialism.

“On Porcelain”

By: Sally Wen Mao

…

the West has attempted to replicate / Porcelain

and failed / Marco Polo tried to give it a name:

porcellana / As he presented a vase to his queen

Named for the translucent / White cowrie shell,

legal tender for the slave trade / A sister word to

porcella / Little hog / Its belly ripe for breeding,

…

This is what ornamentalism illuminates for me. As we move into what feels like a new wave of global conflict with historically orientalized others, as our world is globalized beyond repair, and as the language of “wokeness,” has been diluted, rendered inadequate, and ultimately decimated, we long for new terms upon which we might negotiate justice, peace, and maybe even mere fulfillment.

We might look to aesthetics for political innovations; we might begin with the fruit of considering what objects reveal about personhood, and how cultural objects might help us reconstruct.

We might activate the political power of beauty towards a more inhabitable diversity that recognizes and reconciles hybrid histories of abuse without reclining into easy answers.

“Dreams”

By: Langston Hughes

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.

Hold fast to dreams

For when dreams go

Life is a barren field

Frozen with snow.

There is so much more to be said: on images of the black in “Eastern” art, on Afro-Asiatic relations, on the BRI and how China’s colonization of Africa impacts art, on “solidarity,” “coalition-building,” and proper cultural treatment, and I hope to probe this so-much-more-to-be-said by echoing Cheng’s gesture in motioning toward that which we are too afraid to say at all.

Ornamentalism helps us imagine who we might become. Hybridity gives us a language for aesthetic defiance and for reassembling ourselves through the beauty of our distinct cultural origins and all their objects’ charge.

Culture can be carried with care, and our future can be beautiful in ways we have not dared to imagine. This project of utopianism is one I dare to carry forth, no matter how foreign its earnesty may appear to us now. Even if the hijab is not yet the solution.

To finding that which is,

Alyssa

**If you are new to Quiet Parts, I am a 21-year old poet, and Quiet Parts is my reader-powered poet’s studio where I do things like share poetry, flesh out scholarship, publish my newsletter, and curate guides and recommendations that inspire me.

Once I was the National Youth Poet Laureate, now I am legally an adult and yet so much more a baby than I was. Amongst other things, I am experimenting with form and inspiration and developing a consistent writing practice. For exclusive access to me and my content consider becoming a paid Quiet Patron or perhaps funding the caffeine that sustains my practice.

Thank you for reading so far, I’m so happy you’re here.**

Cheng, Ornamentalism, 1.

All Cheng quotes in this text either come from her book Ornamentalism or her eponymous “Ornamentalism: A Feminist Theory for the Yellow Woman,” published in Critical Inquiry 44 by The University of Chicago.

Over my head but not my heart.